The debate about part-time and full-time work is not only a hot topic in Switzerland. A look at Austria shows that strange ideas are also being discussed there to curb the trend towards part-time work. For example: a bonus of 1000 euros is being distributed to all those who increase their level of employment to 100%. Is something similar necessary in Switzerland?

Switzerland as a positive example

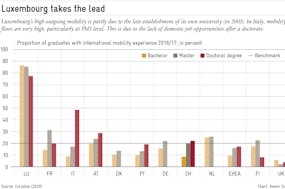

As the figure shows, Switzerland is still in a good position compared to OECD countries, at least when it comes to the (negative) tax incentives resulting from the income tax and social security contributions on wages. The extension of working hours from part-time work is only slightly penalized.

For example, consider the case of a single person living in Zurich who earns the (national) average gross hourly wage and goes from a 50% workload to a 75% workload. The 50% increase in gross salary leads to a 46% increase in net salary. If the workload is doubled from 50% to 100%, income after tax increases by 88%. Only in Hungary, where wages are taxed proportionally, is the progression flatter. This is in stark contrast to Belgium, where a doubling of the workload leads to an increase in net salary of only 50%.

However, the table above should be read with caution when discussing work incentives. It only shows the effects of income tax – and only for the average income. This means that, on the one hand, the picture may be different for other income groups. On the other hand, from an economic perspective, other aspects are also important in determining whether an increase in workload is worthwhile or not. For example, health insurance benefits or childcare subsidies may no longer be available. A comprehensive analysis of work incentives would of course have to take these points into account.

It should also be noted in the table: A flat progression of income tax in the middle range does not mean that the overall tax burden is low. Some countries that achieve top positions in the OECD rankings shown here perform poorly in another key area: VAT. France, Denmark and Hungary, for example, have VAT rates of 20%, 25% and 27%. These countries therefore slow down additional work relatively little (especially in the middle class, as the analysis is limited to average wages), but they squeeze the tax lemons much harder than Switzerland, where the regular VAT rate is 8.1%.

Room for improvement

And because a tax system cannot be assessed using a single key figure, one must temper Switzerland’s good position in the table above. Indeed, one important group suffers more under the current tax structure: married women. Due to the joint taxation of married couples’ income, they generally have higher marginal tax rates in Switzerland than unmarried individuals. This means that married women have less financial incentive to increase their workload, especially if their spouse earns a higher salary.

On the one hand, this systematic disadvantage could be corrected by introducing individual taxation, as currently discussed at federal level. On the other hand, a flatter progression would also solve the problem, for example with a flat-rate tax, as is already the case in some cantons or Hungary. Both would be a step in the right direction, both to achieve a fairer distribution of the tax burden and to distort incentives to work less.